By historical standards, work-related fatalities have fallen 95% in the 20th century. Steven Pinker, a Harvard University psychologist, documents data in his book Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018) estimating that 61 workers per 100,000 employees died in occupational accidents as late as 1913, but by 2015, the number had decreased to 3.2, which is a 95% reduction over a little more than a century.

It’s not just in the United States, however. This encouraging trend can be observed globally. The WSH Institute, which reports research out of Singapore, estimates that 16.4 workers per 100,000 employees died worldwide in 1998. In just 16 years, that number had fallen to 11.3 or 31%. Workplace fatalities seem to be falling by almost 2% every year around the world.

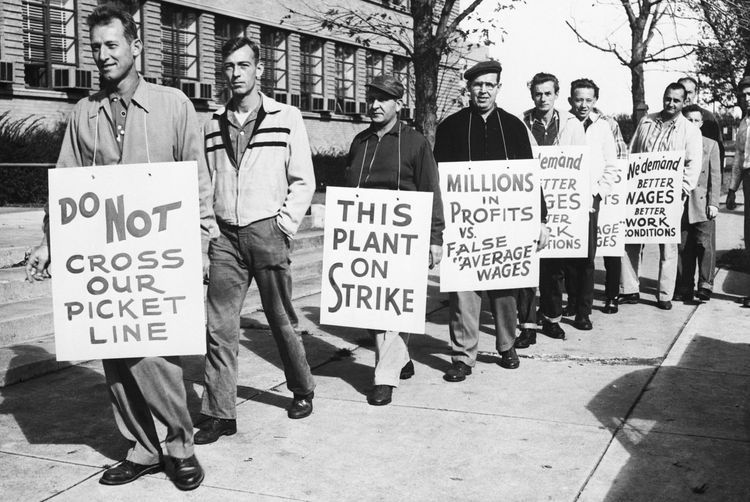

What has changed? Since the Industrial Revolution—a lot. Throughout the 20th century, there have been child labor laws and labor union activism. Strikes, protests, and the organization of unions have helped to organize employees to take collection action. Government regulations also deserve some credit for these improvements.

In 1935, the Wagner Act was passed in order to enable private sector employees to engage in collective bargaining. In 1971, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration was formed, which furthered the cause. But one could also argue that the general improvements in living standards and higher expectations on the part of workers have also played a role.

One of the most dangerous industries worldwide is agriculture. The fatality rate for agricultural workers is seven times higher than all other private industries. Over the years, people have been moving away from jobs on the farm and working in cities. Likewise, jobs with higher risks like coal mining and factories have seen technological advances that have made the work easier and safer. This all comes as good news to workers around the world.